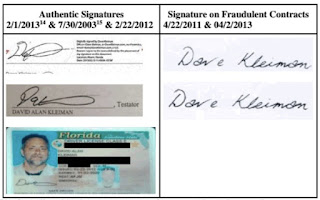

Adding a signature to a document is fundamentally a way of providing assurance that the person whose signature it is has approved of its contents. A signature by itself is, however, not a very secure way of doing this. Handwritten signatures can be easily forged, copied or even machine written. Especially when provided in copied form, there is no definitive way of telling whether a signature on a document is genuine and actually proves that the person did in fact sign the document.

|

| Do these signatures look genuine? |

To get more assurance, it is possible for example to get a notary to certify that a signature is genuine, the notary then being used as a trusted third party that is vouching for the signature being genuine. For further reassurance, the document itself can be protected from being altered by adding ribbon and seals, which provide assurances that the document that has been signed has not changed since being signed. Doing all this takes time and money, so in practice it is often taken on trust that a signed document is genuine. For documents relating to patent proceedings at the European Patent Office, the UK IPO and elsewhere, the office will accept a copy of a signed document and assume that it is genuine, the assumption being that the document was originally hand signed and then copied, provided it looks real.

|

| How can you tell this signature is genuine? |

At risk of stating what should be the obvious, a digital signature is not something that is written by hand or pasted on a computer screen that looks like one written by hand on a piece of paper. It should be clear that this type of signature is far too easy to fake. If spotted, such signatures should be (and often are) rejected. Even if you sign by hand your actual signature on a computer screen, the proof that it was you is non-existent because anyone else could have done the same by copying and pasting an image of your signature from somewhere else, the result being indistinguishable.

A real digital signature is something quite different. A digital signature, if done correctly, performs all the original functions of a genuine original handwritten signature but without the need for an authenticated paper copy. To work, a digital signature must be kept in its original form along with the document it is supposed to be authenticating. Without the code making up the digital signature, in combination with the original document, the signature is meaningless because it cannot be verified, defeating its whole purpose. A common confusion I have seen is when a scanned pdf is presented with what seems to be a digital signature, but the process of scanning has stripped it out, leaving only a mark on a computer file that suggests it was signed. This is, of course, useless and not even as good as a scanned copy of a handwritten signature.

To go back to basics, digital signing at its heart involves asymmetric cryptography. A user who wants to sign something will have a private key, which they keep to themselves, and a public key, which is open for all to see. The user can apply their private key to a document (or, in practice, a hash of a document) to produce a signature string. Anyone else can then use the combination of the document, signature and public key to cryptographically prove that the user's private key was used to sign the document. The signature therefore proves that the document was signed by the user. The only assumption made is that nobody else had access to the user's private key. It is fundamental to the ability to verify the signature that the document and signature are kept together and in their original state. If either is altered by even one single bit, the signature will not validate.

An example of digital signing I have used before relates to how the Bitcoin system works. Bitcoin addresses (P2PKH types) are representations of the public key part of a public-private key pair. The owner of the bitcoin associated with an address is in possession of the private key and therefore only they are capable of 'spending' the bitcoin. In practice, transferring ownership from one address to another involves a process of digital signing, in which the owner signs a transaction with their private key to the effect that only the owner of the private key of the recipient address can then do any further transactions with whatever is sent to that address. Since all transactions are publicly available, anyone can verify how much any particular address contains. Another feature is that the owner of an address can verify that they own it by digitally signing a message linked to the address. An example I have used before is the following:

I, Tufty Sylvestris, confirm that I am the owner of the following address.

bc1quklwszfchvfzpxa7wk8pge7ykczcg0pv54wc8a

IA0TdtltWrzK62rDVw/WkZ36hNOGshhw8UFXySK7VFY9Nv5mQWr6B3aXpDpFH15gPH7uUJsPzlLB/T+eKkXjMWo=

To go back to the principle of signing documents, the message part corresponds to the document. The message is signed with the private key corresponding to the address, resulting in the signature string. Anyone can then verify that the signature is genuine by copying these components into a signature verifying tool, such as the one provided within the Electrum Bitcoin wallet, or one available online. You do, however, have to be very careful that the tool you are using for verification is not in some way compromised or you could be easily fooled.

An additional problem with using just a public-private key pair is that you do not necessarily have a link between the owner of the private key and a specific person unless you have some other way of figuring out who the owner of the private key is. To take a well known example, the owner of the private key to address 12c6DSiU4Rq3P4ZxziKxzrL5LmMBrzjrJX is, beyond any reasonable doubt, the person who was behind the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto because this address was the destination for the very first 50 (spendable) bitcoin that were mined on 9 January 2009.

For any normal use, it is necessary to provide a link between a private key and an actual person. A usual way to do this is for private keys for use in digital signing to be issued and certified by trusted authorities. For the EPO, this is done by a user's private key being securely stored on a smart card issued by the EPO to a patent attorney together with a PIN. With possession of the PIN and the smart card, the attorney can sign a document to the satisfaction of the EPO. Documents can only be signed with physical possession of the card and knowledge of the PIN, providing a decent level of security. This works very well for everyday activities of an EP attorney, who can use their smart card to digitally sign documents that are sent online to the EPO. The same principle can also be used to sign any documents. I can, for example, take any pdf document and apply a digital signature from my smart card that proves I signed the document. The document with its signature attached could then be sent to someone who wanted evidence that I signed it and they would be able to verify with a single click that the signature was valid.

The EPO has recently announced, in the November 2021 issue of the Official Journal, that "a qualified electronic signature" will be "considered to fulfil the legal requirement for a signature with respect to data in electronic form in the same way that a handwritten signature does with respect to data on paper". On the face of it, this seems quite straightforward. Provided the digital signature can be verified, the EPO will accept it. Clearly a signature produced using an EPO-issued smart card will work. Other signatures should also work, such as those issued by Docusign, which are increasingly common. The key, however, is that it must be possible to verify the signature. As a patent attorney, if I am asked whether something will qualify to be used in support of, for example, a request to record an assignment, the answer should be simple. If I can verify it myself, it should be ok. If I am presented with a copied pdf with a stamp stating that it has been digitally signed, the answer is of course no.

Another feature of the new rule is that, as I know from recent personal experience, documents that have been signed on screen and passed off as handwritten signatures are now more likely to be rejected. Under the new provisions, before trying to record an assignment that looks like it might have been signed on a screen rather than by hand, ask yourself whether it looks like it meets the requirements and, if not, go back to your client and ask how the document was signed.