A recent decision from the EPO Boards of Appeal, T 105/11, illustrates a couple of points that should serve as a warning to both patent attorneys and EPO examining divisions.

European patent application 05771127.7, in the name of LG Electronics Inc., reached the end of the line as far as the examining division (ED) was concerned, with oral proceedings held on 30 June 2010. The outcome was that the application was refused for lack of inventive step. The ED issued their decision on 29 July 2010, supported by their grounds for the decision. The applicant's attorney wrote back the next month to indicate an error in the decision, noting that the grounds made reference to an auxiliary request that did not exist. The ED then issued what appeared to be a replacement decision on 6 September 2010, with the grounds amended to correct the error. At this point, the question that might immediately come to mind (at least with the benefit of hindsight) is: what was the correct date to take into account for calculating the periods for filing a notice of appeal and the supporting grounds of appeal? Was it the original date of 29 July 2010 or the later date of 6 September 2010 for the corrected version? The patent attorney responsible for the appeal apparently thought it was the latter. Although a notice of appeal was filed on 23 September 2010, which was in due time for both of the dates, the grounds of appeal were not filed until 7 January 2011, which could only be in time for the later date. The EPO initially processed the appeal to indicate that the notice, fee and grounds had been filed in due time, presumably taking the second date as the one to work from. The Board of Appeal, however, took a different view, at least initially. One they got round to finally looking at the case, in a preliminary opinion issued on 27 November 2015 the Board indicated that the ED did not have the power to withdraw a decision and take a new decision, meaning that the second issued decision could not take the place of the first, but could only correct it retrospectively. The appeal therefore appeared to be inadmissible because the statement of grounds was filed late.

In the subsequent appeal decision, the Board cited various decisions (T 1176/00, T 1081/02, T 830/03, T 993/06 and T 130/07) where a second decision had been issued incorrectly and had been relied on the the detriment of the parties. In each case the Board had decided that the appeal should be found admissible in view of the principle of the protection of legitimate expectations, given that the parties had in each case been misled into thinking that the date of the decision was different from what it actually was. The Board distinguished this case over the previous cases though, because the appellant had explicitly requested that the written decision be corrected. In the Board's view, "the professionally represented appellant should have been aware that the second decision intended to correct as requested by the appellant itself, the first written decision under Rule 140 EPC" (point 1.8 of the reasons). In other words, the attorney should have known that the second decision was not a replacement decision and did not change the original date. Although it could be argued that the apparent confusion was the result of a legal misunderstanding, it was clear that the second decision was not issued correctly and it was this that the appellant had relied on to count the periods for filing the notice and grounds of appeal. The Board then decided that the grounds were deemed to have been filed in time, although "not entirely without hesitation" (point 1.10).

The reason for the Board deciding in favour of the appellant probably also had something to do with the ED being responsible not only for an incorrectly issued decision but also for a number of errors in the decision itself. Firstly, the ED referred to claims that had been filed on 30 July 2009. The applicant had, however, filed different claims on 25 May 2010 before the oral proceedings. The ED's decision was therefore based on claims that were no longer approved by the applicant. The ED also did not annex a copy of the claims to the decision, as advised in the Guidelines for Examination (E-IX, 5). The ED also did not follow the problem-solution approach in their reasons for finding the application to lack inventive step, contrary to the Guidelines (G-VII, 5), making the decision being insufficiently reasoned in violation of Rule 111(2) EPC. The decision was also, the Board's view, unconvincing in other respects, in particular where they had indicated doubt as to whether the technical problem argued by the applicant actually existed. As the Board noted, it is irrelevant whether or not a problem actually exists in the prior art, as the problem is defined as one given to the skilled person as part of the problem-solution approach. Given the numerous flaws in the ED's reasoning, the Board decided to remit the application to the ED and reimbursed the appeal fee.

Other than spotting that the apparently reissued decision was not the one to be relied on, it is not clear to me what the appellant could have done differently in this case, given the catalogue of errors on the part of the examining division. It looks like this is just one of those cases that will have been very frustrating for the applicant, and one that will probably not be settled for a while yet. Let's hope that the examining division have learned some lessons and do better next time.

Thursday 31 March 2016

Thursday 17 March 2016

T 1727/12 - Biogen sufficiency at the EPO?

As every European patent attorney knows, clarity is not a valid ground of opposition. This does not, however, stop oppositions being filed using sufficiency (Article 100(b) EPC) as a disguise for what would otherwise be a clarity objection. The usual outcome of such an attempt is to cause a bit of trouble for the patent proprietor, but for the opposition division to then dismiss the argument as being unallowable. It is, however, sometimes difficult to separate sufficiency from clarity, as they are to some extent linked together. While clarity relates to the claims being clear and concise and supported by the description (Article 84), sufficiency relates to the application disclosing the invention in a manner sufficiently clear and complete for it to be carried out by a person skilled in the art (Article 83). If the claims are not clear, and the application does not help to clarify them, then an argument could be made that the skilled person could not reproduce the invention.

In the UK, following the case of Biogen v Medeva in 1996, the law regarding sufficiency is further entwined with clarity, resulting in two types of insufficiency. The first 'classical' type of sufficiency relates to the skilled person being able to reproduce the invention, given the teaching of the application as a whole and the skilled person's common general knowledge. This corresponds most closely with Article 83 EPC. The second type of sufficiency, which is known from the case as Biogen sufficiency, relates to the skilled person being able to reproduce the invention over the whole scope of the claim. Biogen sufficiency is really then about support in the description, which in UK case law relates closely to whether a priority claim is valid. In the disputed patent in the Biogen case, which related to a DNA sequence for causing a cell to make antigens of the hepatitis B virus, the scope of the claim covered the invention as applied to prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. The priority application, however, only disclosed the invention as applied to bacterial (i.e. prokaryotic) cells. The House of Lords, following Lord Hoffmann's opinion, found that this resulted in the application not being entitled to priority. As a result, the patent was found to be obvious over an intervening disclosure.

It should now be reasonably clear that Biogen sufficiency does not translate well to opposition proceedings at the EPO, because it is tied up with other issues such as clarity and priority. If arguments of the type raised in Biogen v Medeva were raised during opposition, a counter argument would be that these relate to clarity rather than sufficiency and should therefore be dismissed. This did not, however, stop the opposition division in the case of proceedings relating to EP1767375 from raising Biogen sufficiency as a ground for revoking the patent.

The invention in question related to a tape drive for a transfer printer (like the one shown here from Videojet), in which tension on the tape was monitored and maintained between predetermined limits by controlling motors driving a pair of spools. Claim 1 did not specify how the tension was measured, but claim 3 provided means to monitor power supplied to the motors, and claims 4 and 5 provided further detail on how the power was measured. If all this seems vaguely familiar, this is because the case related to a patent that was revoked in the UK in the case of Zipher v Markem in 2008, which was only one of a number of cases involving these parties. The opposition proceedings against Zipher's European patent (since transferred to Videojet Technologies, Inc.), which were initiated around the same time as the court proceedings in the UK, have taken a whopping seven years to complete, with the final appeal decision in T 1727/12 issuing last month.

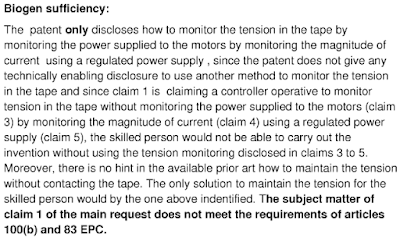

At the conclusion of the opposition in July 2012, the opposition division's sole ground for revocation was sufficiency, as summarised by the following paragraph in the grounds for the decision:

The patent proprietor appealed against the decision, arguing that it was not clear what the OD meant by 'Biogen sufficiency' (although their representative, being a UK based patent attorney, would obviously know what it meant under English law). More importantly though, they argued that the objection was without foundation on the facts of the case. Although claim 1 was broader than the specific description, the skilled person would, the proprietor argued, easily be able to realise the invention using the specification and common general knowledge.

As the Board of Appeal put it, the OD had distinguished between 'classical insufficiency' and 'Biogen sufficiency'. They had found the invention to be disclosed sufficiently clearly and completely for the skilled person to carry it out, thereby fulfilling the classical sufficiency requirement under Article 83. What they had considered the invention to lack though was sufficiency in the sense that the skilled person would not be able to carry out the invention over the whole scope of the claim, since the patent did not disclose other ways of carrying out the invention than those defined in the dependent claims. The Board considered, however, that Biogen sufficiency, as defined by the UK House of Lords, related to Article 84 EPC and not to Article 83, given that the underlying purpose was the requirement for support by the description to ensure that the patent monopoly was justified by the actual technical contribution to the art. The Board was not convinced that the OD had justified the use of Biogen sufficiency in relation to Article 83, and concluded that they had not shown that the patent failed to comply with Article 100(b). Since there were other issues that were left open, including novelty and inventive step, the Board remitted the case to the OD to take a look at these.

What made the OD in this case pull Biogen sufficiency out of the hat to justify revoking a European patent is a mystery to me. Even if it was relevant to the case, using a principle of a national court in proceedings at the EPO is to say the least a bit unconventional. It also looks as if the OD did not even understand what the principle was about. As well as establishing that Biogen sufficiency is not something that should be used in EPO oppositions, the case demonstrates that sufficiency arguments at the EPO, whether raised by the opponent or the opposition division, should be a bit more substantive than simply arguing that the skilled person would not be able to do the invention in another undefined way. Such arguments should rightly be dismissed as being invalid grounds of opposition.

In the UK, following the case of Biogen v Medeva in 1996, the law regarding sufficiency is further entwined with clarity, resulting in two types of insufficiency. The first 'classical' type of sufficiency relates to the skilled person being able to reproduce the invention, given the teaching of the application as a whole and the skilled person's common general knowledge. This corresponds most closely with Article 83 EPC. The second type of sufficiency, which is known from the case as Biogen sufficiency, relates to the skilled person being able to reproduce the invention over the whole scope of the claim. Biogen sufficiency is really then about support in the description, which in UK case law relates closely to whether a priority claim is valid. In the disputed patent in the Biogen case, which related to a DNA sequence for causing a cell to make antigens of the hepatitis B virus, the scope of the claim covered the invention as applied to prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. The priority application, however, only disclosed the invention as applied to bacterial (i.e. prokaryotic) cells. The House of Lords, following Lord Hoffmann's opinion, found that this resulted in the application not being entitled to priority. As a result, the patent was found to be obvious over an intervening disclosure.

It should now be reasonably clear that Biogen sufficiency does not translate well to opposition proceedings at the EPO, because it is tied up with other issues such as clarity and priority. If arguments of the type raised in Biogen v Medeva were raised during opposition, a counter argument would be that these relate to clarity rather than sufficiency and should therefore be dismissed. This did not, however, stop the opposition division in the case of proceedings relating to EP1767375 from raising Biogen sufficiency as a ground for revoking the patent.

The invention in question related to a tape drive for a transfer printer (like the one shown here from Videojet), in which tension on the tape was monitored and maintained between predetermined limits by controlling motors driving a pair of spools. Claim 1 did not specify how the tension was measured, but claim 3 provided means to monitor power supplied to the motors, and claims 4 and 5 provided further detail on how the power was measured. If all this seems vaguely familiar, this is because the case related to a patent that was revoked in the UK in the case of Zipher v Markem in 2008, which was only one of a number of cases involving these parties. The opposition proceedings against Zipher's European patent (since transferred to Videojet Technologies, Inc.), which were initiated around the same time as the court proceedings in the UK, have taken a whopping seven years to complete, with the final appeal decision in T 1727/12 issuing last month.

At the conclusion of the opposition in July 2012, the opposition division's sole ground for revocation was sufficiency, as summarised by the following paragraph in the grounds for the decision:

The patent proprietor appealed against the decision, arguing that it was not clear what the OD meant by 'Biogen sufficiency' (although their representative, being a UK based patent attorney, would obviously know what it meant under English law). More importantly though, they argued that the objection was without foundation on the facts of the case. Although claim 1 was broader than the specific description, the skilled person would, the proprietor argued, easily be able to realise the invention using the specification and common general knowledge.

As the Board of Appeal put it, the OD had distinguished between 'classical insufficiency' and 'Biogen sufficiency'. They had found the invention to be disclosed sufficiently clearly and completely for the skilled person to carry it out, thereby fulfilling the classical sufficiency requirement under Article 83. What they had considered the invention to lack though was sufficiency in the sense that the skilled person would not be able to carry out the invention over the whole scope of the claim, since the patent did not disclose other ways of carrying out the invention than those defined in the dependent claims. The Board considered, however, that Biogen sufficiency, as defined by the UK House of Lords, related to Article 84 EPC and not to Article 83, given that the underlying purpose was the requirement for support by the description to ensure that the patent monopoly was justified by the actual technical contribution to the art. The Board was not convinced that the OD had justified the use of Biogen sufficiency in relation to Article 83, and concluded that they had not shown that the patent failed to comply with Article 100(b). Since there were other issues that were left open, including novelty and inventive step, the Board remitted the case to the OD to take a look at these.

What made the OD in this case pull Biogen sufficiency out of the hat to justify revoking a European patent is a mystery to me. Even if it was relevant to the case, using a principle of a national court in proceedings at the EPO is to say the least a bit unconventional. It also looks as if the OD did not even understand what the principle was about. As well as establishing that Biogen sufficiency is not something that should be used in EPO oppositions, the case demonstrates that sufficiency arguments at the EPO, whether raised by the opponent or the opposition division, should be a bit more substantive than simply arguing that the skilled person would not be able to do the invention in another undefined way. Such arguments should rightly be dismissed as being invalid grounds of opposition.

Tuesday 15 March 2016

A Clear Cut Case

I have mentioned a few times in previous posts the UK IPO's statement that they will only revoke a patent under s73(1A) in "clear-cut cases where the patent clearly lacks novelty or an inventive step". What this actually means is not yet itself clear, as we have only had one revocation so far since the new section came into force in October 2014. Apparently, even if a patent examiner considers that a patent lacks novelty, the IPO will not proceed with revocation if the cited document is a Chinese utility model or if the patent proprietor responds with some arguments about how the examiner got it wrong (see here and here for the examples I have in mind). There must, however, be some cases where the issue is so blindingly clear that there can be absolutely no argument about the examiner's finding of a lack of novelty.

What about a case where a patent is granted and the very same invention is then found to have been disclosed in an earlier published application by the same inventor that was not found by the examiner during prosecution? Such cases must be very unusual indeed, as doing this would be a very silly thing to do for any applicant, and a patent examiner would surely be able to easily find any previous published application by the same inventor when doing a routine search. This does, however, appear to have happened, and has resulted in patent office opinion 02/16, issued on 23 February 2016.

European application 08252964.5, in the name of Shane Kelly as inventor and applicant, was filed on 5 September 2008 without any claim to priority. The application related to a piece of agricultural equipment generally known as a harrow. The main embodiment from figure 1 of the application is shown here. The application was then searched by the EPO examiner, who found some documents and objected on grounds of lack of inventive step, but pointed out that the application could be allowed based on one of the dependent claims. After a couple of rounds of examination, the applicant relented and got the application allowed based on the examiner's suggestion. The application was then granted in January 2012 as EP2160936B1, and has been kept in force in a few EP countries, including the UK, for the past four years.

European application 08252964.5, in the name of Shane Kelly as inventor and applicant, was filed on 5 September 2008 without any claim to priority. The application related to a piece of agricultural equipment generally known as a harrow. The main embodiment from figure 1 of the application is shown here. The application was then searched by the EPO examiner, who found some documents and objected on grounds of lack of inventive step, but pointed out that the application could be allowed based on one of the dependent claims. After a couple of rounds of examination, the applicant relented and got the application allowed based on the examiner's suggestion. The application was then granted in January 2012 as EP2160936B1, and has been kept in force in a few EP countries, including the UK, for the past four years.

A request for a patent office opinion on validity was filed on 11 January 2016, which identified a published Australian application AU2007216912A1, having a publication date of 10 April 2008 (i.e. five months before the filing date of the patent). The request is fairly simply written, and alleges that claim 1 of the patent would be obvious because it is a combination of claims 1 and 8 of the previous publication (suggesting that the request was not prepared professionally). The examiner, however, was quick to point out that the patent was actually not new because it was virtually identical to the previous publication. Figure 1 of the patent (above), which is the main embodiment, is actually the same as figure 6 of the previous publication (below), and the examiner found there was a direct correspondence between every claim of the patent and either a claim or a part of the description in the previous publication. Unsurprisingly, the invention in the patent was found to be not new.

A request for a patent office opinion on validity was filed on 11 January 2016, which identified a published Australian application AU2007216912A1, having a publication date of 10 April 2008 (i.e. five months before the filing date of the patent). The request is fairly simply written, and alleges that claim 1 of the patent would be obvious because it is a combination of claims 1 and 8 of the previous publication (suggesting that the request was not prepared professionally). The examiner, however, was quick to point out that the patent was actually not new because it was virtually identical to the previous publication. Figure 1 of the patent (above), which is the main embodiment, is actually the same as figure 6 of the previous publication (below), and the examiner found there was a direct correspondence between every claim of the patent and either a claim or a part of the description in the previous publication. Unsurprisingly, the invention in the patent was found to be not new.

The proprietor now has until 23 May 2016 to request a review of the opinion, but I think it is very unlikely they will do so. The patent will then stand to be revoked by the comptroller under section 73(1A), which in my opinion is certain to happen.

This case seems to me to be a good example of why the new section 73(1A) is a good thing, because it enables clearly invalid patents to be removed from the register, at least in the UK. Examiners do sometimes miss documents that would be very easy to find (for example in this case with a search for the inventor's name in the same classification), but the result can be a patent sitting on the register providing a deterrent to others that would otherwise be potentially expensive for anyone else to get rid of. Although initiating revocation proceedings at the IPO is very cheap, doing so will expose the requester to costs if they do not win. Even in cases where the case is a clear win, the possibility of adverse costs alone can be a strong deterrent to anyone considering getting a patent out of the way. What the opinions service does is remove this deterrent, and allows such patents to be got out of the way with as little fuss as possible, and with no potential for adverse costs.

What about a case where a patent is granted and the very same invention is then found to have been disclosed in an earlier published application by the same inventor that was not found by the examiner during prosecution? Such cases must be very unusual indeed, as doing this would be a very silly thing to do for any applicant, and a patent examiner would surely be able to easily find any previous published application by the same inventor when doing a routine search. This does, however, appear to have happened, and has resulted in patent office opinion 02/16, issued on 23 February 2016.

European application 08252964.5, in the name of Shane Kelly as inventor and applicant, was filed on 5 September 2008 without any claim to priority. The application related to a piece of agricultural equipment generally known as a harrow. The main embodiment from figure 1 of the application is shown here. The application was then searched by the EPO examiner, who found some documents and objected on grounds of lack of inventive step, but pointed out that the application could be allowed based on one of the dependent claims. After a couple of rounds of examination, the applicant relented and got the application allowed based on the examiner's suggestion. The application was then granted in January 2012 as EP2160936B1, and has been kept in force in a few EP countries, including the UK, for the past four years.

European application 08252964.5, in the name of Shane Kelly as inventor and applicant, was filed on 5 September 2008 without any claim to priority. The application related to a piece of agricultural equipment generally known as a harrow. The main embodiment from figure 1 of the application is shown here. The application was then searched by the EPO examiner, who found some documents and objected on grounds of lack of inventive step, but pointed out that the application could be allowed based on one of the dependent claims. After a couple of rounds of examination, the applicant relented and got the application allowed based on the examiner's suggestion. The application was then granted in January 2012 as EP2160936B1, and has been kept in force in a few EP countries, including the UK, for the past four years. A request for a patent office opinion on validity was filed on 11 January 2016, which identified a published Australian application AU2007216912A1, having a publication date of 10 April 2008 (i.e. five months before the filing date of the patent). The request is fairly simply written, and alleges that claim 1 of the patent would be obvious because it is a combination of claims 1 and 8 of the previous publication (suggesting that the request was not prepared professionally). The examiner, however, was quick to point out that the patent was actually not new because it was virtually identical to the previous publication. Figure 1 of the patent (above), which is the main embodiment, is actually the same as figure 6 of the previous publication (below), and the examiner found there was a direct correspondence between every claim of the patent and either a claim or a part of the description in the previous publication. Unsurprisingly, the invention in the patent was found to be not new.

A request for a patent office opinion on validity was filed on 11 January 2016, which identified a published Australian application AU2007216912A1, having a publication date of 10 April 2008 (i.e. five months before the filing date of the patent). The request is fairly simply written, and alleges that claim 1 of the patent would be obvious because it is a combination of claims 1 and 8 of the previous publication (suggesting that the request was not prepared professionally). The examiner, however, was quick to point out that the patent was actually not new because it was virtually identical to the previous publication. Figure 1 of the patent (above), which is the main embodiment, is actually the same as figure 6 of the previous publication (below), and the examiner found there was a direct correspondence between every claim of the patent and either a claim or a part of the description in the previous publication. Unsurprisingly, the invention in the patent was found to be not new.The proprietor now has until 23 May 2016 to request a review of the opinion, but I think it is very unlikely they will do so. The patent will then stand to be revoked by the comptroller under section 73(1A), which in my opinion is certain to happen.

This case seems to me to be a good example of why the new section 73(1A) is a good thing, because it enables clearly invalid patents to be removed from the register, at least in the UK. Examiners do sometimes miss documents that would be very easy to find (for example in this case with a search for the inventor's name in the same classification), but the result can be a patent sitting on the register providing a deterrent to others that would otherwise be potentially expensive for anyone else to get rid of. Although initiating revocation proceedings at the IPO is very cheap, doing so will expose the requester to costs if they do not win. Even in cases where the case is a clear win, the possibility of adverse costs alone can be a strong deterrent to anyone considering getting a patent out of the way. What the opinions service does is remove this deterrent, and allows such patents to be got out of the way with as little fuss as possible, and with no potential for adverse costs.

Tuesday 8 March 2016

The First Section 73(1A) Revocation

As from 1 October 2014, when section 73 of the UK Patents Act 1977 was amended, it has been possible for a patent to be automatically revoked by the Patent Office following a negative opinion on novelty or inventive step issued under section 74A. As the IPO indicated at the time, such revocation would only be done in 'clear-cut cases', although they did not set out what this would mean in practice. Since then, nine opinions have issued that have found a patent to lack novelty or inventive step. I have been keeping a close watch on how these cases have progressed, and have provided updates here, here, here, here and here. In the first two cases where a decision from the IPO was reached, no action was taken to revoke the patent. The IPO provided no reasoning in either case as to why they decided to take no action.

A decision has now issued in relation to EP1837182, a patent owned by Fujifilm Corporation. The patent, titled "Ink washing liquid and cleaning method" relates to use of a liquid as an ink washing liquid for a photocurable ink in an inject printer system. An opinion on validity was requested by Acredian IP (presumably on behalf of an interested party) in March 2015, raising three documents that the requester considered were relevant. The examiner found, in Opinion 04/15 issued on 4 June 2015, that the claims of the patent were either lacking in novelty or inventive step over the cited documents. The patent proprietor then had three months to request a review of the opinion to contest it, which they did not do. Shortly after this period expired, on 16 September 2015 the IPO wrote to the proprietor's representative inviting them to consider filing amendments. The proprietor did not respond to this in time. The IPO then sent another letter on 22 January 2016 indicating that they were considering revoking the patent. No response was sent to this either. A decision then issued on 19 February revoking the patent. The decision is fairly short, and states in full:

1. An Official letter dated 16 September 2015 explained that the invention of claims of the above patent was not new or did not involve an inventive step and that revocation of the UK Patent under Section 73(1A) might therefore be necessary. The proprietor did not submit observations or proposals for amendment. A hearing was therefore offered in an Official letter dated 22 January 2016 but the proprietor has not asked to be heard.

2. In the absence of any argument to the contrary, I am satisfied that the conditions of Section 73(1A) are met. I therefore order revocation of the UK patent.

Appeal 3. Any appeal must be lodged within 28 days after the date of this decision.This decision is the first that has been taken by the IPO to revoke a patent following a negative opinion. In contrast to the earlier case relating to GB2487996 (which I wrote about here), where the proprietor contested the IPO's initial view that the patent should be revoked, in this case the proprietor did nothing to try to keep their patent. The result should therefore not have been too much of a surprise. Although this is probably generalising a bit too much from only two cases, it does seem so far that the IPO might mean 'clear-cut' to be cases where their initial opinion is not contested. I would like to see this disproved, for example by the IPO defending their view that a patent should be revoked, but at the current rate of issuance of opinions it might take quite a while to see this happen. For now though, it is at least interesting to see that the new provision of section 73(1A) can actually work and that it can be all done (barring any appeal) in just less than one year.

Thursday 3 March 2016

G 1/15 Amicus Briefs

The deadline for filing amicus briefs on the case of G 1/15 regarding partial priority was on 1 March 2016. This was also the deadline set by the Enlarged Board for the EPO President to submit his comments. Now that all comments and briefs are in, the Enlarged Board has indicated that oral proceedings will be held on 7 and 8 June 2016 at the EPO in Munich, and has communicated all of the comments submitted to the parties.

In total, 35 submissions have been filed (36 if you count this late filed submission), including those from the appellant and respondent, as well as the comments from the EPO President. The table below is a brief summary of each of them, indicating what answers each suggests the Enlarged Board should give to the five questions that have been raised, at least as far as I can figure it out. The link in each case will take you to a full copy of each brief.

Although the decision will clearly not be made on a vote, it is interesting to see that 24 of the briefs recommend that question 1 is answered with a 'no', with only 5 suggesting a 'yes'. The remaining briefs either do not address question 1 (Vossius and WSGR) or do not make it clear (at least to me) what the answer should be (Olena Butriy, EPO President and a couple of others).

Just to remind you, question 1 asks essentially whether a claim in a European patent application can be denied partial priority to subject matter in a priority document that is encompassed by the claim. As I have explained in previous posts, my view is that the answer should be a clear 'no', making the remaining questions redundant.

Although most of the briefs have also suggested a clear 'no' to question 1, there are some that have considered that there might be cases where the answer could be qualified with caveats or conditions. Pekka Heino, for example, suggests that partial priority should be refused if the subject matter of a claim only partially overlaps subject matter of the priority document (although this does seem to miss the point in question 1 of the claim encompassing the priority subject matter). Ericsson, who cautiously suggest a 'yes', or possibly a 'no' with caveats, also suggest that there could be exceptions, for example where the second filing proposes an alternative susceptible of replacing a feature disclosed in the first filing. Again, this seems to me to define a case where the claim would not encompass the priority subject matter, so might be dealt with that way. VNONCW, who prefer a 'no' to question 1, go further and hedge their bets by suggesting what the answers to the remaining questions should be in case the Enlarged Board answer with a 'yes'. Another one from epi also goes into how the Enlarged Board should answer questions 2 to 5 in the event the answer to question 1 is a 'yes'.

Out of all the contributions, my personal choices would be those from Bardehle Pagenberg and Delta Patents, both of which are comprehensive and very readable summaries of the situation. Some of the others are worth reading as well, particularly those where a contrary view is taken and/or where an answer is provided for one or more of the other questions. Both Vossius and WSGR do not deal with question 1 at all, for example, but concentrate on question 5, which is whether a parent or divisional application can be prior art under Article 54(3) against an application in the same family.

The comments from FICPI are, of course, also worth a look, since it was a memorandum from them that G 2/98 indicated "can be said to express the legislative intent behind Article 88(2), second sentence" (point 6.4), which this referral is all (or at least mostly) about. FICPI make the very obvious and clear point that any interpretation of G 2/98 that does not fit with the principles laid out in the memorandum and its three examples would be (or, as they cautiously state, appear to be) erroneous.

The EPO President's comments provide, as might be expected, an exhaustive analysis of the case law and background to the question of partial priority, citing the usual sources, and provide some guidance as to how the questions might be answered, in particular at paragraph 144:

In total, 35 submissions have been filed (36 if you count this late filed submission), including those from the appellant and respondent, as well as the comments from the EPO President. The table below is a brief summary of each of them, indicating what answers each suggests the Enlarged Board should give to the five questions that have been raised, at least as far as I can figure it out. The link in each case will take you to a full copy of each brief.

Question 1

|

Question 2

|

Question 3

|

Question 4

|

Question 5

|

|

No

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

No

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

As stated

|

n/a

|

Unanswered

|

|

No

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Alexander

Esslinger (Betten & Resch)

|

No

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

No

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

No

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

No

|

|

No

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

No

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

No

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

No

|

|

No

|

No

|

impossible to answer

|

partial priority must be respected

|

No

|

|

Unclear

|

-

|

-

|

G 2/98 in context of EB disclosure test

|

No

|

|

Yes

|

unclear

|

as stated

|

unclear

|

No

|

|

No

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Yes

|

?

|

?

|

?

|

?

|

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

G 2/98

|

n/a

|

Yes (?)

|

|

No

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Infineum

(applicant / proprietor)

|

No

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

No

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

No

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

No

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Klaus

Mikulecky (Respondent)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

As stated

|

n/a

|

Yes

|

No

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

No

|

|

?

|

|||||

No

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

No

|

|

?

|

?

|

?

|

?

|

?

|

|

No

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

No (with caveats)

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

No

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

No (?)

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

No (preferred)

|

Yes (if q1=no)

|

Based on T 571/10

|

n/a

|

No

|

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

No

|

|

No

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

No

|

Although the decision will clearly not be made on a vote, it is interesting to see that 24 of the briefs recommend that question 1 is answered with a 'no', with only 5 suggesting a 'yes'. The remaining briefs either do not address question 1 (Vossius and WSGR) or do not make it clear (at least to me) what the answer should be (Olena Butriy, EPO President and a couple of others).

Just to remind you, question 1 asks essentially whether a claim in a European patent application can be denied partial priority to subject matter in a priority document that is encompassed by the claim. As I have explained in previous posts, my view is that the answer should be a clear 'no', making the remaining questions redundant.

Although most of the briefs have also suggested a clear 'no' to question 1, there are some that have considered that there might be cases where the answer could be qualified with caveats or conditions. Pekka Heino, for example, suggests that partial priority should be refused if the subject matter of a claim only partially overlaps subject matter of the priority document (although this does seem to miss the point in question 1 of the claim encompassing the priority subject matter). Ericsson, who cautiously suggest a 'yes', or possibly a 'no' with caveats, also suggest that there could be exceptions, for example where the second filing proposes an alternative susceptible of replacing a feature disclosed in the first filing. Again, this seems to me to define a case where the claim would not encompass the priority subject matter, so might be dealt with that way. VNONCW, who prefer a 'no' to question 1, go further and hedge their bets by suggesting what the answers to the remaining questions should be in case the Enlarged Board answer with a 'yes'. Another one from epi also goes into how the Enlarged Board should answer questions 2 to 5 in the event the answer to question 1 is a 'yes'.

Out of all the contributions, my personal choices would be those from Bardehle Pagenberg and Delta Patents, both of which are comprehensive and very readable summaries of the situation. Some of the others are worth reading as well, particularly those where a contrary view is taken and/or where an answer is provided for one or more of the other questions. Both Vossius and WSGR do not deal with question 1 at all, for example, but concentrate on question 5, which is whether a parent or divisional application can be prior art under Article 54(3) against an application in the same family.

The comments from FICPI are, of course, also worth a look, since it was a memorandum from them that G 2/98 indicated "can be said to express the legislative intent behind Article 88(2), second sentence" (point 6.4), which this referral is all (or at least mostly) about. FICPI make the very obvious and clear point that any interpretation of G 2/98 that does not fit with the principles laid out in the memorandum and its three examples would be (or, as they cautiously state, appear to be) erroneous.

The EPO President's comments provide, as might be expected, an exhaustive analysis of the case law and background to the question of partial priority, citing the usual sources, and provide some guidance as to how the questions might be answered, in particular at paragraph 144:

"According to the Enlarged Board, subject-matter in general enjoys priority if it is derived from the priority document using the disclosure test. Subject-matter encompassed by a generic "OR"-claim enjoys priority if it is derived from the priority document using the disclosure test and if it is one of "a limited number of clearly defined alternatives". A generic "OR"-claim is explicitly recognised as being capable of enjoying partial priority for subject-matter that it encompasses "either in the form of a generic term or formula, or otherwise".194 It appears to be incompatible with this definition to require alternative subject-matters to be "spelled out as such". Hence, the strict approach seems to be at odds with the Enlarged Board's jurisprudence. At the same time, the "broad" approach may be too abstract in the light of the requirement for "the claiming of a limited number of clearly defined alternatives." Thus, especially in the technical fields of chemistry and biotechnology, the burden on the public to identify a high number of alternatives should be taken into account." (emphasis added)

This suggests that the answer to question 1 might be a qualified 'No', depending on whether the "limited number" test from G 2/98 should be taken into account. The President is clearer on question 5 though, and states at paragraph 146: "A proper assessment of partial priority entails a negative answer to question 5. Sound arguments based on the purpose and function of divisional applications in the patent system, and within the EPC, would likewise suggest a negative answer". How anything but a clear 'No' answer to question 1 could lead to a negative answer to question 5 is not clear to me, but at least the President (or, more accurately, whoever wrote the comments for him) is clear that the answer should be 'No' regardless of how it is arrived at.

I have not analysed each of the briefs in detail, so there will undoubtedly be some other interesting points I have not yet noticed. Any comments noting these, or making any other relevant point, would be gratefully received.

Note: This post has been updated extensively since it was originally posted on 3 March as further comments and briefs appeared on the register.

Note: This post has been updated extensively since it was originally posted on 3 March as further comments and briefs appeared on the register.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)