Does copyright subsist in the 'Bitcoin File Format'? This was the question in Wright & Ors v BTC Core & Ors [2023] EWHC 222 (Ch), where Mellor J found earlier this year that it did not because the subject-matter was "not expressed or fixed anywhere" (paragraph 62). On appeal ([2023] EWCA Civ 868), Arnold LJ decided that all that was required was that "the structure be completely and unambiguously recorded" (para 69). The claimants did therefore have a "real prospect of successfully establishing the fixation requirement is satisfied" and the appeal was allowed. Do the claimants now therefore have a prospect, real or otherwise, of establishing that this fixation requirement is satisfied?

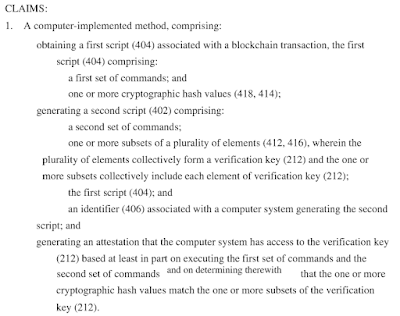

Firstly, for those who may be unfamiliar with the term (which is possibly understandable since it appears to have been invented for the legal proceedings), what is the "Bitcoin File Format"? According to the claimants, it is "the original work consisting of the structure of each block of the Bitcoin Blockchain" (referring to a Schedule which is unfortunately not publicly available, but which was written in 2022). The Bitcoin File Format (BFF) is therefore the way that data is arranged in each Bitcoin block. The basics of this are explained on the Bitcoin Wiki page for the Genesis Block, which in raw hexadecimal form looks like this:

|

| Genesis Block (annotated) |

|

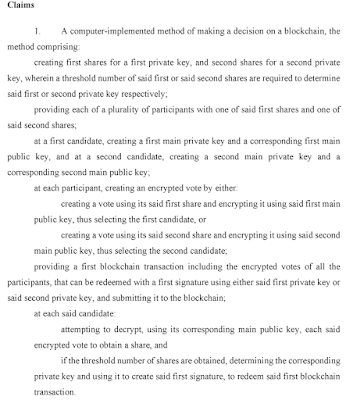

| An example XML template (from here) |

"It is most revealing that, despite all these opportunities, the Claimants have not filed any evidence to the effect that a block contains content indicating the structure, as opposed to simply reflecting it. By 'content indicating the structure', I mean, by way of a crude example, a flag or symbol in the block which signals 'this is the start of the header' or 'this is the end of the header', or an equivalent of the sort of content which is found in an XML file format. Whilst I entirely accept that each block conforms to the structure described in Schedule 2 to the Particulars of Claim and is an instance or manifestation of that structure, the absence of such evidence confirms my initial view that, whether one considers the point at which the first, second or subsequent block(s) were written embodying the structure of the file format, nowhere was the structure of Bitcoin File Format fixed in a copyright sense in a material form in any of those blocks" (paragraph 57).

This is the key point on which the judgment was overturned on appeal. It is indeed clear that the format of the block is not evident from the block itself, unless you know what you are looking for, but Arnold LJ considered that this did not actually matter. The block did have a format, but the fixation of this format did not need to be in the same place. He summarised the requirements that the claimant would need to meet in order to establish that copyright subsisted in the BFF, which were set out (in paragraph 61) that:

i) the Bitcoin File Format is a work;

ii) it is a work that falls within one of the categories of protectable work specified in the 1988 Act;

iii) the work has been fixed;

iv) the work is original; and

v) the work qualifies for copyright protection under the 1988 Act.

The only point in contention was iii), which Mellor J found was not met. Arnold LJ considered that, while it was correct that the work, that is to say the structure, must be fixed in order for copyright to subsist in it, it did not necessarily follow that content defining the structure was required in order to fix it. All that is required is that the structure be completely and unambiguously recorded. The claimants did therefore have a real prospect of successfully establishing that the fixation requirement was satisfied, provided they were able to provide evidence of the structure being recorded from the right time, i.e. from before the alleged infringements.

An odd feature of this case is that, in the original Particulars of Claim (PoC), the claimants alleged infringement of: i) Database Right in the Bitcoin Blockchain (discussed by me here); ii) Copyright in the Bitcoin File Format; and iii) Copyright in the Bitcoin White Paper. There was no mention of the Bitcoin software itself, which as it turns out is actually where the Bitcoin File Format is fixed. The structure of the Genesis Block, for example, is in fact completely defined in the original Bitcoin software. It therefore strikes me as strange that the claimants chose not to refer to this as providing the fixation requirement, particularly as Mr Wright claims to have written the software himself and would therefore presumably know where to look. Given that Arnold LJ has decided that the work and the fixation requirements can be met by different things, perhaps this will be what the claimants come up with next in their attempts to enforce copyright in the Bitcoin File Format.